The Agrievolution Alliance.

As an engine manufacturer and power solution provider, Perkins has long enjoyed a strong relationship with agricultural original equipment manufacturers (OEMs). For this issue of Powernews, we turn our attention to the Agrievolution Alliance, the global voice for more than 6,000 agricultural equipment manufacturers around the world.

In an interview with Powernews, we got the lowdown from Agrievolution’s Secretary General Charlie O’Brien and Chairman Ignacio Ruiz.

Describing itself as ‘an advocate for global mechanisation for sustainable agriculture’, the idea for what would become the Agrievolution Alliance first emerged in 2008 at the first Agrievolution summit hosted by FEDERUNACOMA, the Italian Farm Machinery Manufacturers’ Association.

“It was suggested that manufacturers could benefit from a broader reach, more people working together,” recalls Charlie. “The summit brought together key leaders from manufacturing and put them in a room with the world’s agricultural ministers and key influencers. Then get everyone talking.”

Among the issues discussed at that first summit were, unsurprisingly, emissions standards. Sixteen years later, the topic’s still important, if not more so – but Charlie says it underlined the importance of being able to share information as a group, and to use that interaction and understanding to help manufacturers around the world prepare for the more stringent legislation everyone knew was coming.

“It showed there was a need, a desire even, to have this kind of collaboration, in which ideas could be exchanged, and concerns shared more rapidly and easily amongst like-minded organisations,” Charlie says. “Proof of concept, as it were, led to formal establishment in 2012.”

Today, it’s still a talking shop, but with added tools. “Data, for example,” says Charlie. “We’re now rich in data, something that enables Agrievolution Alliance to review and assess what’s going on in different regions of the world, comparing retail, wholesale, different equipment sectors, trade flows – you name it.

“Individual members can look at that and see the trends, follow the trade. That’s very valuable.”

Those members now comprise 12 national and regional agriculture and equipment associations, plus a recent welcome to the German agricultural society DLG under a new Strategic Membership category – partners who share the Alliance’s vision and support its efforts.

Perhaps what’s most remarkable about the Alliance’s own evolution is how it’s avoided becoming an inward-looking organisation, instead becoming a strong and consistent advocate for agriculture around the world.

“That means different things in different parts of the world,” stresses Charlie. “Here in the U.S., advocating for agriculture means promoting precision, sustainability, the latest technologies, all within the industry. Outside, we’re also educating those who are making the decisions about the industry as a whole – the U.S. Government, for example.

“Around the world, there are more and more people that don’t know anything about agriculture. They have no familiarity with it. We spend a lot of time on education in more developed countries, but it’s a different story in emerging economies.”

There, Charlie explains, the Alliance has more basic aims – not necessarily the latest and great technologies, but simple, practical mechanisation.

“Bringing power to an environment where it will raise yields and increase productivity? That can really change farming practices in some parts of the world.”

Despite the contrast in the Alliance’s work as an advocate, Charlie says its basic remit is the same: communicating the significance of applying power to agriculture and making clear the benefits of mechanised agriculture at whatever level is appropriate.

“A lot of our advocacy is concerned with regulation,” he says, “and trying to make for ‘good’ legislation. Unrealistic expectations of farmers or manufacturers, or unnecessary barriers to trade – that’s the sort of thing we try to deliver for our members.

“A lot of regulations are very good, and very helpful, especially when it comes to our focus on sustainable agriculture. But they need to make sense, and it’s our input that can help create a regulatory environment in which manufacturers and end-users can be comfortable.”

The interaction between manufacturers and end-users is essential for the advancement of agriculture, suggests Ignacio Ruiz, the Alliance’s Chairman. “Agricultural technology has been responsible for the growth in productivity we’ve needed to feed a growing world population.

“The main technological asset is machinery,” he points out. “It’s primarily concerned with soil, but also distribution and application of necessary inputs, as well as harvesting and maximising quantity and quality of the final crop.”

But what drives innovation in machinery and equipment? “Farmers’ experience with crop production and the research conducted by scientists is certainly influential in machinery design, form and function,” Ignacio observes.

“But machinery manufacturers also invest a lot of resources in their own research. That’s how we arrive at innovations that help to meet legislative requirements for environmental protection, operator health and safety, and return on investment.”

Ignacio points to precision farming and digitalisation as being a tipping point. “Applied to agricultural machinery, these will change agricultural production as we know it.

“The brake on that happening is the gap between technology supply and demand, which is widening as farmers’ disposable incomes stagnate.”

Another big factor shaping development and direction of agricultural mechanisation comes back to the big issue discussed at the Alliance’s conception: the industry’s responsibility to reduce emissions. If agriculture’s said to contribute 24 percent to emissions of global greenhouse gases (GHGs), how is the Alliance encouraging members to mitigate this?

“All machinery manufacturers are reducing GHGs, of course, by taking advantage of innovations in engine technology, transmissions, and other components installed in tractors and self-propelled machines,” Ignacio points out.

“But the demand for agricultural machinery is not high enough to absorb the GHG emission reductions implemented by manufacturers. Increase in machinery costs can cause farmers to shift towards used and older equipment, which can result in a contrary effect.

“So it’s our role to inform manufacturers of their obligations to meet sustainable development goals, such as GHG reduction, but also to use our grasp of data to show how legislative measures can be compromised in the real market.

“By highlighting the inefficiencies or shortcomings that impact competitiveness and fail to achieve the policy objectives, we move to avoid any serious compromises in agricultural productivity caused by farmers’ inability to adopt new, cleaner technologies.”

Another factor to consider, says Ignacio, is the evidence of diminishing returns to land productivity. A 2022 paper (Steenwyk et al[i]) showed that despite work per hectare increasing by a factor of 4.5 between 1950 and 2012, land productivity increased by a factor of only 2.75.

“The paper reveals how more work is needed for every unit of land, in order to feed a growing population,” says Ignacio. “But if more farm work is needed, then we’ll need more energy too – farm machine efficiencies are beginning to plateau. And increasing final energy consumption will work against climate goals.

“The adoption of new energy technologies, while necessary, can’t come with costs that are not generally affordable, or else new sustainable energy sources will meet a market that’s not yet economically ready to adopt them.”

Charlie points out that there are other ways to reduce emissions from agriculture. “We can minimise carbon loss and increase carbon storage through increasing adoption of new tillage practices – no-till or lo-till. Again, that comes down to the interaction between farmers and manufacturers: where’s the innovation, will it be matched by farmers’ willingness to adopt new ideas and practices?”

In addition to the challenges of emission reduction, Charlie points to geopolitics as another major concern for the Alliance and its members. “We’re only too aware of the knock-on effect that has for agriculture as a whole. What we don’t always appreciate is the difficulty that presents for our members, in terms of trade.

“Despite a trend towards free-trade agreements, five or ten years ago it was noticeably easier to ship equipment between different parts of the world. And the trickledown effect is that while we’re still working with the same people, they and us are finding constraints in sharing information or other interactions. It’s a strain for any organisation trying to bring together a global membership or dealing in global issues.”

But the biggest challenge is something to which anyone who works in agriculture can relate. Agriculture has become a ‘bogeyman’ to many people.

“It’s a consequence of the modern industrialised, urban world. Fewer and fewer people are touching agriculture,” he admits, “which means even fewer people have a good understanding of the industry.

“This lack of understanding is a real problem, which is only going to get worse as the industry continues in consolidation. So how do we make sure that agriculture is not seen as the enemy? How do we show that it’s an industry that’s able to provide a sustainable environment while putting good healthy food on the table?

“We’ve got to get the message across: food doesn’t come from the grocery store, it ends up there – and how it gets there is kind of important for all of us.”

[i] Steenwyk, P., Heun, M.K., Brockway, P. et al. The Contributions of Muscle and Machine Work to Land and Labor Productivity in World Agriculture Since 1800. Biophys Econ Sust 7, 2 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41247-022-00096-z

-

Perkins® 904 Series: pushing the boundaries

The new model will deliver up to 129 kW (173 hp) and 740 Nm (546 lb ft) at 1500 rpm, from a compact 3.6 litre engine.

Read more -

High‑reliability power systems: The silent guardians ensuring data centre uptime

Ensuring uninterrupted performance is non-negotiable, at the heart of that reliability sits the diesel-powered generator.

Read more -

Built to make a difference: The new 5000 Series is driving progress around the world

Providing dependable power output up to 2500 kVA for standby and 2250 kVA for prime applications.

Read more -

Powering forward: Richard Hemmings on innovation, reliability and what comes next

Powernews caught up with new VP Richard Hemmings to learn more about his new role.

Read more -

A future full of momentum for Golden Arrow Marine

Building on a legacy of over 1000 Perkins engines supplied and 62 years of hands-on experience.

Read more -

Rewriting the rules of power: The electric unit driving the next wave of innovation

The Perkins battery-electric power unit continues to attract interest among original equipment manufacturers (OEMs).

Read more -

Connectivity delivers real-time insights

Perkins’ collaboration with Trackunit, delivering real-time insights to customers, increasing productivity in the field.

Read more -

Rental equipment runs on uptime

For industrial equipment rental, excellent technical support and parts availability is a necessity.

Read more -

Powering ahead in agriculture

To mark Agritechnica's 'Celebrate Farming Day', Powernews spoke to Andy Curtis, Customer Solutions Director at Perkins.

Read more -

New marine propulsion engines

Clever configuration options fulfil the current and future requirements of the industry.

Read more

Also in this issue

-

New marine engines exhibited

A new range of auxiliary marine engines were shown at METS.

Read more -

California: the state that feeds America

Adrian Bell dives into the history of Californian agriculture.

Read more -

Seeing the unseeable

The importance of thermal fluids simulation.

Read more -

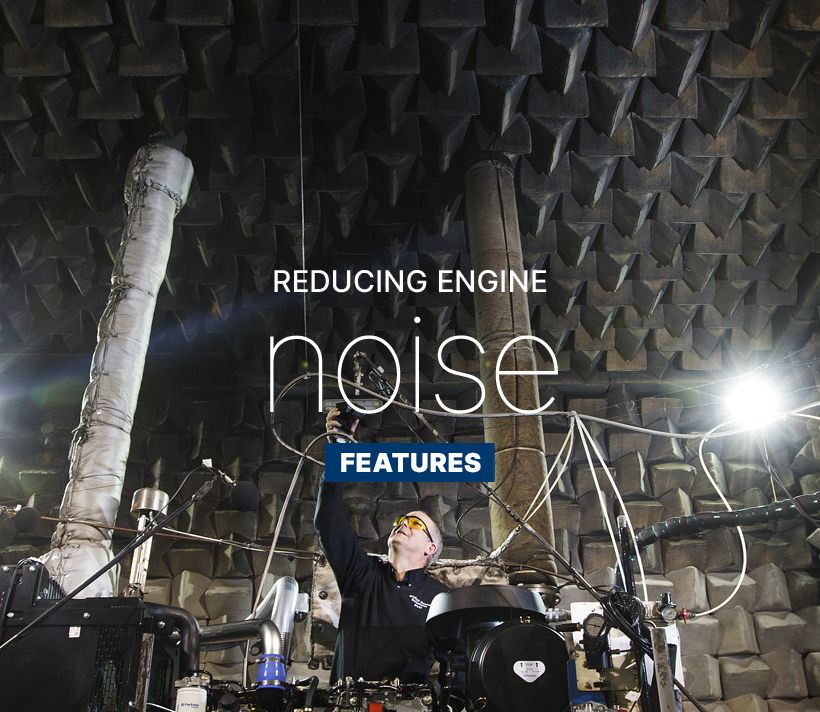

Reducing engine noise

How ‘noise chambers’ help Perkins build quieter engines.

Read more -

Interview with Ann Brown

Meet our Vice President of facility operations.

Read more